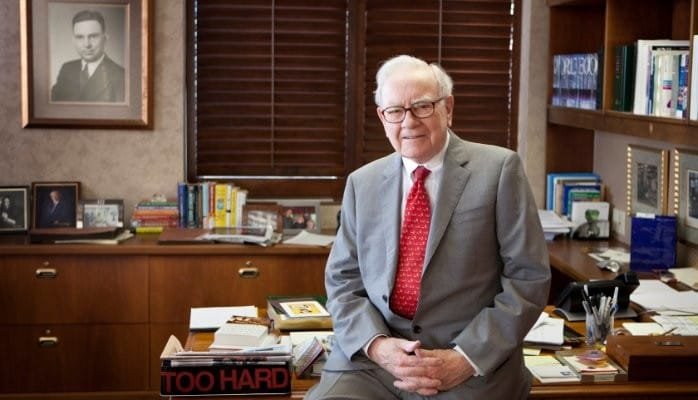

Warren Buffett: A Tribute to the Greatest Capital Allocator in Corporate History

By the end of 2025, the curtain will fall on one of the most remarkable capital allocators in the history of business. Warren Edward Buffett, the Oracle of Omaha, has decided to officially stepped down as CEO of Berkshire Hathaway after over 60 years at the helm. Buffett’s philosophy in business and investing has and will continue to shape generations of leaders in areas of business, investing, capital allocation, risk management, and even life itself.

His departure marks the end of an era—but his teachings, principles, and stories will echo for decades to come.

Buffett was a master capital allocator —a skill he cultivated over a lifetime and which became the central driver of Berkshire’s compounding machine. Let’s explore how he did it, from the lens of capital allocation.

Early Hustler: From Pinball Machines to His First $10,000

Warren Buffett’s love for business began not in a boardroom but in a library. At an early age, he discovered a life-changing book titled “One Thousand Ways to Make $1,000.” It was filled with ideas ranging from running a stamp dealership to breeding rabbits. He devoured it, and the book made him realise that wealth could be built systematically and compounded over time.

Soon after, Buffett was delivering newspapers, or knocking on doors to sell chewing gum, Coke bottles, and magazines. He started collecting abandoned golf balls to resell. At 11, he bought his first stock—Cities Service Preferred—for $38 a share. The price dipped, he panicked, then sold for a small gain. The lesson in patience stuck with him for life.

Later, he scaled up. With a friend, he bought used pinball machines and installed them in local barber shops. They reinvested the profits to buy more machines, eventually selling the business for over $1,000. By the time he was 15, Buffett had earned over $2,000 delivering newspapers—equivalent to over $25,000 today. He bought a 40-acre Nebraska farm and hired a tenant farmer to run it. By the time he finished high school, Buffett had saved over $10,000—an extraordinary amount for a teenager in the 1940s.

Capital Allocation Lesson: Even in his teens, Buffett mastered the basics of capital allocation: find low-cost assets that generate recurring cash flow, reinvest earnings into more productive ventures, and avoid unnecessary consumption. The idea he gleaned from “One Thousand Ways to Make $1,000” wasn’t just to earn—it was to compound. Every dollar today is worth many dollars in the future due to the power of compounding – a principle that would shape his entire career.

Ben Graham and the Foundation of Value Investing

After graduating from the University of Nebraska at age 19, Buffett set his sights on studying under a man he called “The Dean of Wall Street. Benjamin Graham was the co-author of Security Analysis (1934), an influential book that laid the foundation for value investing, and later The Intelligent Investor, which Buffett would call “by far the best book about investing ever written.”

Buffett enrolled at Columbia Business School in 1950, specifically because Graham was teaching there. In Graham’s classroom, investing wasn’t just theory—it was practical, immersive, and empirical. Students were required to study individual companies from the real world. Class sessions involved analysing a specific stock’s financials and market valuation. Graham encouraged his students to think independently, dispassionately, and rigorously.

But perhaps the most enduring insight Buffett took from Graham wasn’t just about numbers—it was about behaviour. Graham taught that the investor’s worst enemy is often himself. Fear, greed, impatience, and crowd psychology lead to poor decisions, even with good information. He introduced the allegory of “Mr. Market,” a manic-depressive business partner who offers to buy or sell his interest daily at wildly fluctuating prices. The intelligent investor, Graham explained, must view Mr. Market’s emotions as opportunities—not guides.

Buffett absorbed these teachings deeply. He realized that mastering investor psychology was just as crucial as mastering financial statements. He also adopted Graham’s relentless focus on intrinsic value—the idea that every stock has a true worth, based on its ability to generate future cash flows, regardless of what the market says today.

Capital Allocation Lesson: Graham’s classroom was Buffett’s laboratory for learning rationality in capital deployment. He internalised the principle that capital should only be allocated when there is a clear discrepancy between value and price, and that staying psychologically grounded was the only way to identify and act on such discrepancies. He also learnt that capital allocation is not just math—it is judgment, temperament, and discipline.

In case you’re a Ben Graham fan, check out our Ben Graham Top 10 Quotes Canvas Print:

Canvas Print with Ben Graham Top 10 quotes and caricature

Elevate your office with Ben Graham top 10 quotes on a premium canvas. This wall art features a unique caricature and Graham’s timeless investing wisdom. Its a thoughtful gift for investors, CEOs, and business owners.

The GEICO Revelation

In 1951, shortly after enrolling at Columbia, Buffett stumbled upon GEICO, an insurance company in which Graham was the chairman. Curious, Buffett decided to dig deeper. One Saturday morning, with no appointment, Buffett boarded a train to Washington, D.C., and walked into GEICO’s headquarters. The office was closed, but a janitor let him in. There, by pure chance, he met Lorimer Davidson, GEICO’s future CEO. Davidson spent hours with the young Buffett, explaining the company’s business model, economics, and competitive position.

Buffett realised that unlike its competitors which relied on a network of agents to sell policies, GEICO went direct-to-consumer, dramatically lowering its distribution costs. Furthermore, it specifically targeted government employees, a demographic that tended to be lower-risk. This created a powerful combination: low acquisition costs and low loss ratios—the holy grail of insurance underwriting.

GEICO had a structural cost advantage. It was also growing rapidly, since more people with government jobs were purchasing cars, which needed to be insured. At the time, GEICO was trading at around 7x earnings, which Buffett believed was dramatically cheap relative to its long-term earnings power.

So, what did Buffett do with this insight? He bet big. He invested most of his net worth into GEICO stock. It was one of his first major capital allocation decisions, and it showed two key traits that would define his career: a willingness to act decisively when he had high conviction, and the ability to understand a company’s long-term economics better than the market.

Buffett eventually sold the GEICO stake for a tidy profit, but the story didn’t end there. In 1976, after a period of mismanagement nearly bankrupted GEICO, Buffett started buying GEICO shares again. By 1996, Berkshire acquired the entirety of the business. GEICO would go on to become one of Berkshire’s crown jewels.

Capital Allocation Lesson: GEICO taught Buffett the importance of durable business models, cost advantages, and prudent underwriting. More importantly, it taught him that when you truly understand a business’s moat and economics, you don’t nibble—you bet boldly. Great capital allocators don’t diversify for the sake of it; they concentrate when the odds are overwhelming.

Buffett Partnerships and Early Deals

By 1956, at age 25, he started the Buffett Partnerships and to manage just over a $100,000 of capital from family and friends. Over the next 13 years he compounded their capital at an annual rate of 29.5%, far outpacing the Dow’s 7.4%.

Buffett’s strategy during this period was heavily influenced by Graham’s concept of “cigar butt” investing—buying stocks so cheap that even a small puff of remaining value could yield a profit. He scoured thinly followed corners of the market, often buying shares in obscure or mispriced companies that were trading well below their liquidation value or net current assets. These weren’t glamorous businesses—they were often troubled, tiny, or ignored—but they were statistically cheap.

His capital allocation style was bold and concentrated. Traditional portfolio managers diversified widely. But when Buffett found an idea he had deep conviction in, he didn’t hesitate to make it count. He would allocate 25% to 40% of the Partnership’s assets into a single stock if he believed the margin of safety and upside were compelling enough. In rare cases, he even bought controlling stakes and became involved in the company’s operations, often installing trusted managers or improving governance.

Examples from this era include:

- Sanborn Map Company: A tiny map-making business whose stock was worth far less than the value of its investment portfolio. Buffett liquidated its investments and returned cash to shareholders, including himself.

- Dempster Mill: A windmill and farm equipment company. Buffett bought a controlling stake and sent a young partner, Harry Bottle, to improve efficiency and cut costs. They turned the business around and made a significant profit.

- National American Fire Insurance: Another undervalued insurer trading at a steep discount to book value.

Capital Allocation Lesson: During the years of the Buffett Partnerships, Buffett refined a key principle: that great capital allocators don’t think in terms of stock names or ticker symbols—they think in fractions of businesses. He sought asymmetric risk-reward setups where the downside was minimal but the upside could be many multiples of the initial investment. When such opportunities arose, he didn’t spread himself thin—he bet meaningfully. This disciplined yet bold approach laid the groundwork for how he would allocate capital at scale later in Berkshire Hathaway.

Berkshire Hathaway: From Textile Dud to Financial Giant

Warren Buffett’s 1965 takeover of Berkshire Hathaway wasn’t one of his finest capital allocation decisions—at least, not at first. He had been buying stock in the New England textile manufacturer since it traded below its book value. He was hoping to make a modest gain by either closing down the business and selling off its assets. Or turnaround the business and improving its profitability so that he can sell it on to someone else. However, he learnt rather quickly that the textile business was extremely competitive and that Berkshire didn’t have a competitive advantage. He would later confess that buying Berkshire Hathaway was a mistake, and he would have been better off if he had never heard of it.

The textile operations were already in decline, plus, foreign competition, low margins, and lack of pricing power made it a capital sinkhole. But instead of liquidating the company, Buffett did something different: he used Berkshire Hathaway as a permanent capital base—from which he could invest in better businesses.

One of the first and most important pivots he made was into insurance. He acquired National Indemnity in 1967 and later GEICO (fully in 1996), among others. Insurance appealed to Buffett not for the premiums or the operational income, but for its “float”—the pool of money insurers hold between collecting premiums and paying out claims. Float, if managed wisely, functions as low-cost or even negative-cost capital for investment.

However, Buffett soon learned that owning insurance businesses wasn’t as simple as investing their float. In the early years, some of Berkshire’s insurance subsidiaries struggled with poor underwriting, inconsistent profitability, and undisciplined pricing. Writing bad policies meant that float came with future liabilities that outweighed any investment returns.

Recognizing this, Buffett pivoted again—this time toward reinsurance, a more complex but potentially more profitable segment of the industry. In reinsurance, insurers themselves buy insurance to protect against large or catastrophic losses. But this business required sophisticated risk assessment and pricing discipline; that’s where Ajit Jain came in.

In 1986, Buffett hired Jain—an Indian-born, former McKinsey consultant with an analytical mind and deep understanding of insurance risk. Jain built a world-class reinsurance operation within Berkshire, taking on complex, bespoke deals that others avoided. With Jain running the underwriting, Berkshire’s insurance operations became a reliable and lucrative generator of float—and a fortress of disciplined risk management.

Berkshire’s billions of dollars in float, fueled Buffett’s investment empire. From owning stocks like Coca-Cola, Apple, and American Express to buying entire companies like BNSF Railway and Precision Castparts, insurance float was the raw material of the Berkshire snowball.

In fact, Buffett and Munger even found other businesses outside of insurance which had a float. Hence cash was received before it needed to be utilised for expenses and servicing customers. A prime example was Blue Chip Stamps, a company Buffett and Munger began acquiring in the late 1960s.

For Blue Chip Stamps, retailers were the customers: they paid for stamps in advance to receive books of trading stamps, which they then gave away to shoppers as loyalty rewards. Shoppers collected the stamps over time and later redeemed them for merchandise. Crucially, there was a long delay between when Blue Chip received cash from retailers and when shoppers redeemed their stamps—if they ever did. This delay created a pool of low-cost “float,” similar to insurance premiums, which Buffett could use to invest in other businesses.

Buffett was also attracted to businesses with negative working capital or deferred revenue models—such as See’s Candies, which received holiday season payments before delivering its product, and businesses with high recurring revenues and low capital needs. These enterprises mimicked the insurance float dynamic, offering Buffett opportunities to reinvest idle cash at high returns—an essential pillar of his capital allocation strategy.

Capital Allocation Lesson: Buffett’s pivot from textiles to insurance was an important capital reallocation decision. First, he admitted a mistake. Then, he sought an industry where capital could compound. But most importantly, he recognized that skill gaps are an obstacle to capital efficiency—and solved it by hiring experts like Ajit Jain. Great capital allocators know when to pivot, when to delegate, and how to convert short-term liabilities into long-term assets.

Brands with a Moat

Warren Buffett evolved from a “cigar butt” investor into a buyer of wonderful businesses —a shift greatly influenced by Charlie Munger. He was especially drawn to companies with strong pricing power, an intangible but critical competitive advantage. He also noted that brands like Wrigley’s, Coca-Cola, had strong mind-share, in addition to a strong market-share. These brands could raise prices without losing customers, meaning they had the ability to earn high returns on capital year after year.

Take See’s Candies, for example, which Buffett described it as a business with “untapped pricing power” and “a moat built by customer loyalty and brand.” At the time, it was earning only a few million dollars a year. But with little need for reinvestment, its returns on capital were extraordinary. Buffett would increase the price of See’s candy every year, and would find that the customer’s demand for See’s was unaffected.

Other iconic brands that he invested in followed similar attributes:

- Gillette dominated razor blades with near-monopoly status.

- Dairy Queen was loved by customers and the franchisor had minimal capital needs.

- Apple Inc., represented a new kind of brand: one embedded into people’s lives. Buffett, once a tech skeptic, admired Apple’s customer loyalty. He was also attracted to its enormous cash flows, and its ability to raise prices and retain market share.

Capital Allocation Lesson: With companies like See’s, Coca-Cola, and Apple, he found capital-light engines that required little but printed a lot of cash. This cash was sent to the Berkshire head office in Omaha which would further fuel Buffett’s snowball.

Weathering Crises: 2000 and 2008

Two defining moments in modern financial history—the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and the global financial crisis of 2008—illustrate how Buffett’s disciplined capital allocation and opportunism set him apart from the crowd.

Saying “No” When It Was Most Difficult

In the late 1990s, Wall Street and Silicon Valley were swept up in the dot-com euphoria. Startups with no earnings—or sometimes, no revenue—were being valued in the billions based on hope, hype, and fluffy user metrics. Most investors, including many sophisticated institutions, rushed into these “new economy” companies, fearing they’d miss out on the future.

Buffett famously sat out.

Why? Because he refused to allocate capital to businesses he couldn’t understand or confidently value. Buffett’s discipline came from his training under Ben Graham: the value of a business is the present value of future cash flows. Buffett didn’t focus on clicks, eyeballs, or momentum. Most dot-com firms had no proven business model, no pricing power, and no clear path to profitability. Allocating capital into these ventures would’ve been speculation, not investment.

Buffett was ridiculed at the time. Media commentators called him a dinosaur who “just didn’t get it.” But when the bubble burst in 2000, wiping out trillions of dollars, Buffett’s restraint looked prophetic. He preserved capital and avoided catastrophic losses—proving once again that not losing money is the first step in compounding wealth.

Capital Allocation Lesson: Great capital allocation is not just about finding where to invest—it’s knowing when not to invest. Buffett’s refusal to chase irrational exuberance protected Berkshire’s capital and preserved dry powder for when real opportunities would arise.

The 2008 Financial Crisis: “Be Fearful When Others Are Greedy, Be Greedy When Others Are Fearful”

While the dot-com era tested Buffett’s patience, the 2008 global financial crisis tested his boldness.

When the financial system nearly collapsed after the failure of Lehman Brothers, the financial markets were desperate for liquidity. Buffett, holding tens of billions in cash and short-term U.S. Treasuries, was one of the few players ready and able to deploy capital at scale—and on his terms.

He made a series of high-profile, sweetheart deals that showcased how Berkshire Hathaway’s reputation and Buffett’s prudence gave him enormous bargaining power:

- Goldman Sachs: Buffett invested $5 billion in preferred shares yielding 10% annually, along with warrants to buy common stock at deeply discounted prices.

- General Electric (GE): A $3 billion investment, again in preferred shares with 10% annual dividends and generous warrant coverage.

- Bank of America (2011, slightly post-crisis): A $5 billion investment in preferred stock with a 6% yield, plus warrants to purchase 700 million shares at a fixed price—eventually yielding billions in profits.

In each case, Buffett was not merely investing in a rebound—he was getting paid generously to wait, while securing optionality through warrants if the company recovered. These were asymmetric bets—heads he won big, tails he still got paid.

These deals also worked because Buffett brought not just money, but credibility. In times of panic, a Buffett investment acted as a vote of confidence. That reputational capital, built over decades, became a strategic advantage—allowing him to extract better terms than other investors.

Capital Allocation Lesson: In a crisis, liquidity is power. Buffett’s conservative cash management and aversion to leverage positioned him to act when others couldn’t. Berkshire’s balance sheet was a fortress and a strategic reserve which Buffett deployed into deals with limited downside and immense upside.

Capital Allocation Lessons for Business Leaders

Warren Buffett understood that capital allocation was the CEO’s ultimate responsibility. Many public company CEOs struggle with capital allocation. They often fail to reinvest wisely. They squander shareholder capital on overpriced acquisitions, excessive stock buybacks at market peaks, or low-return vanity projects. Often, their decisions are driven by quarterly earnings pressure, Wall Street expectations, or misguided empire-building instincts, rather than sound financial logic.

The most common mistakes CEOs make are:

- Overpaying for Acquisitions: Many executives chase growth through M&A, but overpaying for businesses that don’t earn adequate returns destroys long-term value. Also, these acquired businesses need to be integrated into the existing business, which is often a tricky task that management teams struggle with.

- Poor Timing on Buybacks: Companies often repurchase stock when it’s expensive (to “signal confidence”) and pull back when it’s cheap. This is the exact opposite of what sound capital allocation looks like.

- Dividend Rigidity: Maintaining or growing dividends for the sake of optics, even when better uses of capital exist

- Lack of Return Metrics: Some CEOs fail to rigorously assess the return on invested capital (ROIC) when approving new projects.

What Buffett and Berkshire did differently is the following:

- Rational Capital Deployment: Buffett evaluated every capital decision — from acquisitions to buybacks — through the lens of expected return per dollar. If no attractive opportunities exist, he would let the cash pile up.

- Decentralization with Accountability: Berkshire owns dozens of subsidiaries, where each manager runs their business independently. But capital allocation decisions are centralized at the top, where discipline is fiercest.

- Avoiding “Diworsification”: Buffett refused to deploy capital for the sake of pure growth or diversification. He also didn’t see it fit to invest in one’s ’22nd best idea’.

- Flexible Use of Cash: Buffett believed in opportunistic deployment of cash either internally or via acquisitions. For long periods, Buffett and Munger sat on huge amounts of cash and did nothing, whereas when the right opportunity came along, they acted quickly and decisively.

- Culture of Long-Term Thinking: Buffett wasn’t influenced by quarterly earnings pressure. Berkshire’s structure and leadership allowed it to operate with a multi-decade horizon, which enabled compounding.

Conclusion: The Enduring Blueprint of Capital Allocation

As Warren Buffett steps down after more than six decades at the helm, one of his greatest legacies is his mastery of capital allocation. He taught the world that capital allocation is not just a financial task, but a strategic and moral responsibility.

To summarise, these are the lessons to take away from Buffett’s masterful capital allocation:

- Capital allocation is not just math—it is also judgment, temperament, and discipline.

- Great capital allocation often means waiting years for the right pitch — and then swinging hard.

- Never forget Rule #1, ‘Don’t lose money’. Protect the downside, the returns will take care of itself.

- The best allocations have limited downside and meaningful upside. ‘Heads you win big, tails you don’t lose much.’

- Investing in capital light, cash generative businesses is a great way to let compounding work its magic.

- Great capital allocation is not just about finding where to invest—it’s also knowing when not to invest.

Buffett’s brilliance wasn’t about forecasting trends or predicting the winners — it was about staying grounded in principles, doing simple things extremely well, and having the temperament to wait for fat pitches. In a world of complexity and noise, he offered clarity and calm.

As business leaders, investors, and entrepreneurs look to the future, they would do well to ask themselves at every decision point: “What would Warren do with this dollar?”

P:S: If you love Warren Buffett, you might enjoy our limited edition Buffett Figurine where he’s waiting for the big fat pitch!

Warren Buffett Figurine – Limited Edition

Warren Buffett Figurine – add a touch of timeless wisdom to your space with unique collectible. Crafted with cutting-edge full-color 3D printing technology, this vibrant figurine is durable, high-quality, and shipped in a premium magnetic gift box. Perfect for your library, study, or as a unique gift for fans of the Oracle of Omaha.

You might also like other unique collectibles from our Charlie Munger and Warren Buffett Collections: